Interview with Erik Scollon at Recology

/The Artist in Residence (AIR) Program at Recology is a staple of the San Francisco arts community. In operation since 1990, Recology has given over 120 professional artists and over 30 student artists (including myself) the opportunity to source materials from the city’s dump. The resulting work spans all media and practices, offering artists a glimpse into the untold stories of a discarded city. The current residents—Erik Scollon and Cathy Lu—typically work within a ceramic practice. I sat down with them to chat about their time at Recology, and how the experience relates to the world of ceramics.

Matt Goldberg: Your ceramic work ranges the spectrum from high to low fire, sculptural to functional, object to performance. Do you think that methodology made it easy to embrace the material possibilities at Recology? Was it difficult to start picking objects?

Erik Scollon: No, it was too easy. In undergrad, I had an instructor tell me in reference to the ceramic studio, "Erik you're a bottom-feeder," and I don't think it's an insult even though it sounds like one. She was noticing how I’d just wander around the studio and find the scraps of stuff and figure out how to put it together. Specifically, collecting other students' trimming scraps from porcelain and using that for my casting slip. Which, to me, was the easiest way to get casting slip going.

MG: And could be seen as a conservation effort.

ES: A little bit. I didn’t think of it so much as conservation but as time-saving. Here's these materials, they're already small and dried out, which is exactly what I need for making porcelain slip. It's sort of conservation, but it’s more taking advantage of the things you find.

So starting here, the very first day we had our orientation and Deborah said there's a tour coming in tomorrow and they will be here at 9:30 AM, you should bring some work in because you haven’t had a chance to make anything yet and I just thought, there's no way I'm going to do that. Hauling stuff back and forth, especially ceramics, because it's breakable.

The previous artist, Carrie Hott, had left a bunch of audio tapes, so I grabbed those and the first thing I made was rope out of 27 different audio tapes strung together using rope-making techniques.

ERIK SCOLLON STUDIO, RECOLOGY. IMAGE COURTESY OF the artist.

I thought at the time it was going to be a one-off. I gave myself the informal challenge of making one thing a day while I was here just because I knew it was gonna take me awhile to get up and running. I also knew at the end of my time here school was going to be starting. I teach at CCA and this semester is going to be particularly busy. I feel like I didn’t have the luxury that others sometimes do to play around for a month.

MG: A couple things that come to mind for me within that, first with the rope—I'm trying to draw lines into your ceramic practice—that's similar to coils. Like the first move in this studio was, okay, let's make some coils. Does it feel that way?

ES: I think what carried over for me were the ways that I work were more similar than the process. For example, with ceramics I'll make a lot of things and bring them all up together slowly. Where I'm working on this thing and pause while it's drying then I'll work on this thing, and I'll pause and come over to this and I come back around again and suddenly everything’s dry, so I put it in the kiln to bisque. Then I glaze everything all together, then put it all in the kiln so everything finishes all at once. And that's totally what I've done here, even though I don’t need to. Nothing is totally finished, everything’s a good 90% of the way right now, and there's no reason for that.

Erik Scollon studio, Recology. Image Courtesy of Matt Goldberg.

MG: And what do you feel is that finishing move, the way a glaze fire would be?

ES: Right now, a lot of it is placement and arrangement and paying attention to the aesthetics of things. And also really focusing in conceptually on what I’ve been working with.

Someone else said this originally and I borrowed it: there are hunters and farmers, and hunters are conceptualists who go out and have an idea and find the materials to make that idea come to life. Farmers kind of know where they’re going but don't necessarily know what they’re going to get. Say you plant your crops and you have to tend to things and they slowly emerge and you have to sort of weed things out until you finally end up with food at the end, but it might take a little while. So I think of myself as much more process-oriented.

MG: Farmer?

ES: Yeah process farmer. It's easy to think that hunters are more conceptual than farmers because they start with the idea and then they go make something that matches it.

One of the reasons I was attracted to ceramics is that there's a knowledge and embodiment and movement and physical relationship to things. That art should be a kind of discovery, not just an illustration of an idea. It's a kind of philosophy that your practice is with your body and with your eyes. Like on the postcard—the large blue inflatable. I like the idea that you can interact with it. Your body is in relationship to the thing, it’s not just a visual.

MG: And in that piece, the materials being used—arguably the biggest material—is air. Which is the thing you didn't have to source from the dump. You're almost minimizing the PDRA (Public Disposal Recycling Area) space in order to control what’s happening in the studio.

ES: Yes.

MG: You had mentioned school starting up. How do you view teaching as a part of your practice?

ES: I think sometimes teaching is a form of personal research. You're following something that you're interested in and you have a research team in there all sort of trying out different versions of that same idea. So that you suddenly have 15 people that are picking up that thing or idea you’re interested in and trying out all these different ways. You get to see how they work and learn from them. You get to see what they discover. You also get to find out what you don’t want to do, which is also nice.

MG: In that role, is there opportunity or responsibility in shaping what the future of Bay Area ceramics looks like? Do you feel like you’re steering it a certain way?

ES: I think more than anything I'm trying to undo a lot of the received ideas about ceramics. I have pretty strong opinions about the way it was brought into academia and how it was kind of screwed up and there was a lot of information lost along the way.

There are some really interesting juxtapositions that happened in the Bay Area. Both Edith Heath and Peter Voulkos were making work at the same time, both involved with different institutions, and both working with this emerging idea of ceramics. Peter Voulkos sort of played off a bunch of abstract expressionists, artistic lone-genius posturing.

MG: And partying.

Peter Voulkos at his Glendale Boulevard studio. Image: the getty museum. http://blogs.getty.edu/pacificstandardtime/files/2011/08/PeteAtGlendale-Blvd-studio_1959.jpg.

ES: He was definitely a showman. Whereas Edith Heath was much more interested in thinking about ceramics as her version of industrial design. And I think it’s too bad that with both of them starting from the same place that he got all the attention where she didn’t get quite as much as she deserved.

So I'm interested in making that visible for students for many reasons. One, let's talk about institutional bias and sexism, why we're paying attention to one person and not the other. But more importantly what are the things we lost by not being able to think about artistic practice as being user-centered, collaborative in its making, slow, and design-focused. The designs of Edith Heath made back in the 50's are still in production today.

MG: And they're gorgeous.

ES: Because she really slowed down, whereas over here there's a guy in the studio who's just like cranking out stuff. So Edith Heath is taking years to find the perfect form and we're bragging about how Peter Voulkos went through a ton of clay in a week.

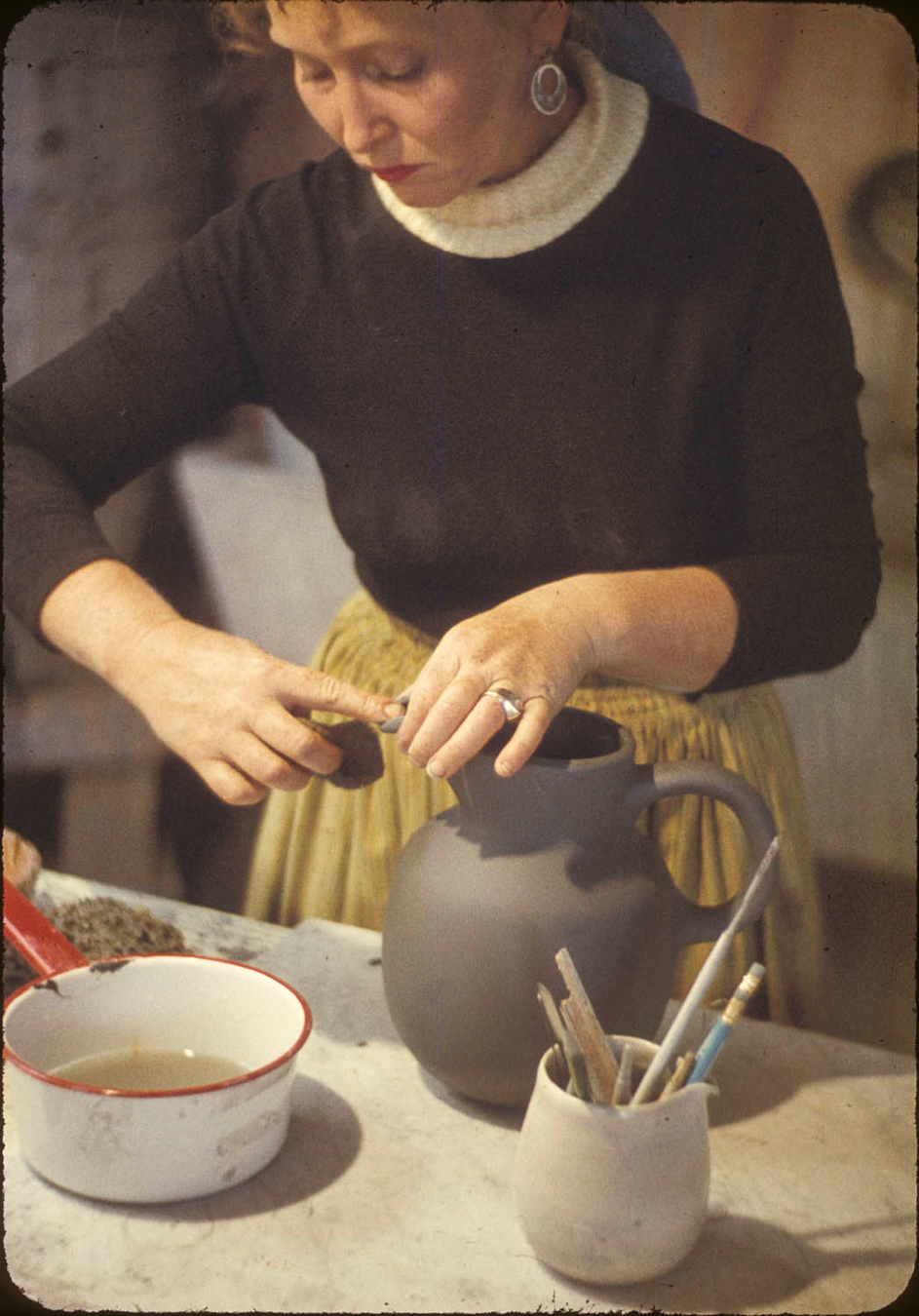

Edith Heath. Image: Atomic Ranch. https://www.atomic-ranch.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/edith-heath-1.jpg.

Most textbooks when talking about ceramics, especially ceramics history, talk about Voulkos, but no one talks about Edith Heath in ceramics history. And so reclaiming that so students can understand. When we think of ceramics we think of it through this institutional lens, like the practice of ceramics is usually housed within the fine arts department. I'm always telling students, that's great, there's lots of things that you're learning, but what are all the things you're not learning because ceramics is in fine arts instead of design.

When we say ceramics, what do we think we mean? It's rare that we mean what Edith Heath is doing. When we say ceramics, we never mean toilet manufacturing. We usually think of it as this individually-directed, solo, studio practice-oriented expression of a person's thing, but that's such a small fraction of all the ceramics in the world that are made. So when we say ceramics, how did we get to understand it from that spot.

The practice of ceramics within the fine arts institutions is the legacy that we’ve inherited today. The goal in teaching is to have students become much more critical thinkers—using ceramics history in service of some of those larger ideas. How to ask really good questions and check assumptions and recognize that just because this is the way people are doing it right now doesn't mean it's the way people have always done it.

MG: So bringing that into this space and residency, do you feel like this is new territory for a ceramic practice? Are you the torchbearer of what a ceramic practice can look like and the forms it can take? Or is this totally separate?

ES: The funny part of everything I just said is that I practice more like an artist than a designer. The questions about clay type and kiln temperature and technique can get really tired really quick. Or that even that you should be so totally wed to one material and not explore a bunch of others. I think that's important. I don’t think of this as anything I should model for students, but you don’t have to dig your heels into this one thing and only do that for the rest of your time, there are lots of ways you can take your view of the world and push them through a bunch of materials. I think that’s the one thing that has held on here is the physicality and materiality and process-oriented making.

MG: In the Voulkos/Heath argument, somewhere in there is an idea of awareness of output—about consideration. More material conscious. You go through a ton of clay in a week and then we have all these massive sculptures to deal with for the rest of time.

ES: The proposal I made for Recology I didn't come anywhere close to making. Part of it is because I got here and just saw all these amazing things. But I had pulled some of those materials I was interested in using—the things I talked about in my proposal—I pulled that stuff aside and I've been thinking about how I can slow down and use some of those.

Right now the most interesting for me is this piece where I stripped the magnetic data off the plastic tape and it's somebody's 50th wedding anniversary.

MG: Seeing the magnetic data collected and compiled in a glass bottle is a pretty charged object; it's also an urn. That's already part of the vocabulary that you came in with. Do you like going in the PDRA, do you feel like you thrive in there? Or is it too much sometimes?

ES: It goes back and forth. Sometimes I go in and I feel like I'm on top of it, where I can go in and pick out what I want right away. There was one day about a month into the residency where I had pulled in enough stuff and the studio was starting to fill up. I'd made some things but hadn’t really gotten anywhere yet and I wasn’t quite sure what I was doing. I kept getting sort of overwhelmed by that and I felt a little paralyzed like I wasn't getting anything done while I was here. So I'd be sitting here not doing anything, I might as well go shopping and get more stuff. Then it's like, “Oh my God, I have a studio full of trash, what am I doing?”

I was having a hard time dealing with all the trash and waste and thinking about what my responsibility is to these materials. I felt overwhelmed by that and being overwhelmed would lead to not doing anything so I would go back in and do it all over again and get more stuff. The next five days I intentionally wore shorts and left my boots at home so I couldn’t go in. There's a little bit of FOMO that happens, like “Oh, somebody is dropping off something amazing and I need to be there.” And just saying, yeah that's something, who cares. Right now I'm still hoping for the right flat screen.

MG: So what's your ideal studio day?

ES: I get really seduced by the latest idea and the new shiny things. So I've really forced myself to put ideas down in my notebook and sit on them for a long time before I start making something. Because I know that if I come up with an idea then go in the studio and start making it—which is super fun and feels really rewarding—I'm never happy with it in the end.

MG: You're subscribing to the Edith Heath philosophy.

ES: Yeah, I work better when I take my time and think about it before I start. It'd be fun to get up in the morning, go to the coffee shop and read something and make some sketches then go into the studio and start making them—that sounds super fun to me—but I know that a month from now it would be like, “What was I doing?”

MG: And then you have a responsibility for those things.

ES: Then I have to figure out what to do with them. The last thing I did in the ceramics studio before starting here was smash up all my failed projects and put them in a ball mill so they would tumble until it smooths all the edges off and turns into a kind of gravel.

Erik Scollon studio, Recology. Image Courtesy of the artist.

MG: The way you’re talking about it is that it's liberating that you don’t have to do that - you don’t have to hold on to this stuff that you’re making. Where in ceramic work, where I guess you were destroying your old projects Baldessari-style. But a lot of people hold onto what they make, their hands are in it, it’s permanent. You keep those objects usually for a long time. But here it’s a little more fleeting or less attached because there's no cost involved, it was thrown out anyway, that risk is minimized. Does it feel like the work you've made embraces that?

ES: It's such a weird relationship to materials here. The heart of this show is really going to be based on the first two things I found.

MG: Which were what?

ES: The tapes that were left over from the last resident. They left a lot of stuff behind like a sort of catch and release. It's just what I was cued into—like, “Oh I've had this idea of VHS tape rope in the back of my head for a long time, there's that.”

But literally the first thing I picked up out of the PDRA on the very first day I went in was all of these blue jackets that were dumped by a parking app startup. And I had used them before and I thought why'd they dump all their jackets here? Then I looked it up online that they had gone out of business, and that's how I found out. It was like, well I can delete that off my phone now. Not gonna use that anymore.

MG: And those stories happen over and over again in this space.

ES: Yeah. So that was the first two things that I found. So with those jackets I pulled them up in the shopping cart and brought them back. It's this weird thing where they were trash 30 seconds before I got to them and picked them up. And as I started thinking about ideas as to what I could do with it they become more special and weirdly precious. Because I was thinking if I want to make an inflatable—and I had made two other test inflatables to help me figure it out. I had made a small plastic one and was like, nope too small. So then I made a huge one and was like, nope way too big. I knew that I wanted to use those and make it count, but I couldn’t experiment on the material itself because I would use it all up.

Erik Scollon studio, Recology. Image Courtesy of the artist.

I have to make this work right because I can’t go shopping for more of this. There's no jacket store, this is it. And that paralyzed me for just a little bit. When I'm working with clay it's easy to just go get more, or just recycle what you've got. Just smash it back down and its clay again. Whereas once you start cutting up stuff too small, you either have to sew it and you can tell where the seam is, or change your idea. So that cycle is strange.

And I'm even having a hard time letting go of some of the scraps and the cut pieces. It feels like it’s my responsibility just because I pulled them out of the dump once.

MG: You feel like you shouldn't throw them back in?

ES: Intellectually I rationalize I should totally throw them back in, like don't make yourself responsible for someone else's trash. But am I responsible for it now that I've pulled it out once? I don't know. I don't think so, but maybe.

MG: I think those burdens are part of the experience.

ES: For sure. It's so weird. Like going through all that. The first thing I made here then threw away it was like, oh yeah, you can do that, it's fine.

Erik Scollon takes on the histories and traditions of ceramics by reworking the techniques of blue and white porcelain, upending our associations with the color saturated world of ceramic hobby glazes, and by creating performative and participatory projects centered on ceramics or ceramic objects. By moving from porcelain to stoneware, high fire to low fire, functional to sculptural, object oriented to performance, he investigates issues of taste, class, gender, and queerness.

Born in Rochester, Michigan, he received his BFA from Albion College, and an MFA in Ceramics along with an MA in Visual and Critical Studies, both from California College of the Arts. A committed educator, Scollon teaches at the University of California at Berkeley and at California College of the Arts. His work has been seen at museums, galleries, craft fairs, design blogs and gay biker bars. He is represented by Romer Young Gallery and he currently lives and works in San Francisco, California.

Matt Goldberg is an artist working in San Francisco where he runs the ceramic programming at SOMArts Cultural Center. Goldberg is a graduate of the San Francisco Art Institute (MFA 2015) and has participated in residencies at Recology (2015) and the Palo Alto Art Center (2016). His ceramic and assemblage sculptures remix American pop cultural icons through a comic, cut-and-paste aesthetic.