Carving Nightmares: Clark Ashton Smith's Sculptures within the H.P. Lovecraft Circle

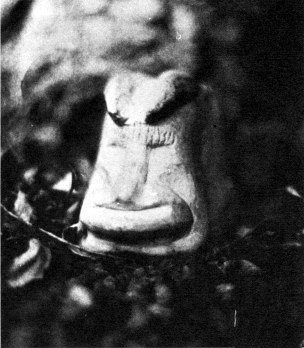

/A ghastly chalk oval—a totemic monster in miniature with ringed, chiseled eyes and an elongated nose carved down to a puckered, screaming mouth, the tongue comically protruding.

The small figurine is a stone carving in talc by writer Clark Ashton Smith, one of the masters of weird fiction—a field whose introduction exchanged the earlier ghoulish and vampiric stock characters of the ghost story and horror genres for some of the earliest science fiction and fantasy creations, including Azathoth, Shib-Niggurath, and Cthulhu.

This sculpture, Moon Dweller, is one of several hundred similar carvings Smith produced during the first half of the twentieth century. These two- to five-inch tall sculptures generally inspire and interpret terror, giving a face to the nightmare creatures described in Smith’s fiction and that of other writers.

The sculptures were used for cover images on published collections of stories, recorded as enlarged and grainy black-and-white photographs. In these images, the sculptures were blown out of scale from the original and staged in a way that highlighted the strangeness and increased the drama of the small models through high contrast lighting.

With Moon Dweller, the sculpture is positioned in the midst of a dark, unfocused background. The black-and-white photograph shows the small carving as if gasping for breath, perhaps asphyxiating in the dust of leaves and small detritus collected around its base.

Most of these carvings show the face and body of a hybrid creature with distorted features and a smooth, nondescript surface pitted by minute imperfections, cracks and natural veins of the mineral. In this case, the sculpture’s lips and eyes form roughly-hewn, concentric rings, while smaller circles pierced in its cheeks form secondary mouths, or perhaps scars or tumors. From below the mouths, tentacles are laid across its chest like suspenders. The background is mottled black and gray, as though in a Gustave Doré etching where storm clouds approach, emblematic of an unearthly and dramatic reckoning.

After seeing Smith’s artwork, writer H.P. Lovecraft wrote, “His work is extremely bizarre & distinctive, & generally represents nameless monsters & landscapes of other planets & other universes. He can draw vegetation that suggests horror in a thousand different forms, while his grotesque heads (generally of monstrous insect-men) are surely nightmares of the first order.”[1]

In keeping with this, the photograph is marked by a harsh light, heightening the image’s drama and washing out the cracks, crevices, and marks of the stone. The figurine appears pinned in place and unable to move. The creature looks horrific yet horrified.

Smith carved his grotesque statues to depict forms from his own imagination or those dreamed up by other weird fiction writers, figuring the nightmare creatures they published in fantastical stories in three dimensions.

It should be noted that Lovecraft’s legacy (and in turn, the writers who were in conversation with him) have been closely identified with white supremacist histories valorizing European civilization at the expense of all others. In his letters, Lovecraft has referred to other cultures as “a bastard mess of stewing Mongrel flesh without intellect, repellent to the eye, nose and imagination,”[2] and his poetry and writings have prompted recent articles like Phenderson Djeli Clark’s essay “The ‘N’ Word Through the Ages: The ‘Madness’ of H.P. Lovecraft.” As a result, the resemblance between Smith’s sculptures and Pacific Islander art should be read in the same vein as Pablo Picasso’s direct appropriation of African artifacts.

In addition to this fraught history, Smith found more site-specific inspiration for the disfigured and distorted faces of his sculptures in weathered forms naturally found in the rocks he collected, [3] which he described as “fragments of primordial bas-reliefs, or small prehistoric idols and figurines.”[4]

Smith and Lovecraft, as part of a set of amateur and published writers following on the heels of Edgar Allan Poe and Lord Dunsany, invented stories of the grotesque and horrific fit for a modern age in which superstitions had been overturned by contemporary scientific advancements. Much like Georges Bataille and the Surrealists of the 1920s, they took up the question of the formless and modernity but in a uniquely American way.

The sculptures, as much as the published short stories, are notable for communicating the fears and modern anxiety of a shared set of American writers in the early 20th century.

Perhaps the largest influence on both Smith’s nightmare carvings and the imagination of weird fiction’s writers in the H.P. Lovecraft circle was their correspondence, allowing them to collectively partake in each other’s dreams of unknown horrors and phantasms. Through letters and discussion, they forged a unique literary community based on unconscious thoughts and shared dreams.

Dreams were always at the center of their discussions, serving as the template for many of their stories and character names as with Azathoth, Nyarlathotep, and the Fungi from Yuggoth.[5] One of Smith’s sculptures was the result of a vivid series of recurring nightmares in which he found himself in a deep, subterranean cave filled with hundreds of small stone carvings similar to the one he eventually sculpted. Other dreams were darker. In 1912, Smith had suffered an attack of tuberculosis and a nervous breakdown, which left him weakened and gave him horrific nightmares that would recur throughout his life. [6]

Although Smith’s dreams served as a source of personal inspiration, it was only through the social structure of written correspondence and amateur magazines that the Lovecraft circle’s dreams could travel and mutate, forming the Cthulhu mythos and other supernatural worlds that all the writers would contribute to. Therefore, it was Lovecraft’s and others’ passion for sharing their stories which provided the environment for Smith’s sculptures to powerfully impact the tales authored by other writers at that time.

Often, stories were published through pulp magazines like Weird Tales; however, many stories did not make it into print. Instead, the writers mailed handwritten and carbon-copied pages of their manuscripts to one another.[7]

These letters alongside Smith’s sculpture became handy templates for sharing the writers’ images of various terror-inspiring demons, inspiring new stories and artwork in the process.

Ultimately, the weird fiction writers produced both literary and visual artifacts recording their fascination and regurgitation of horror. While each author or artist was fairly estranged from the others, they functioned within a collective unconscious, building a shared dream world through postal correspondence and amateur press magazines that stretched from Providence to Florida and California.

In the iridescent, roughly polished forms of Smith’s sculptures like Moon Dweller and others, one can see the materialization of these collective nightmares in their expressionistic features: protruding eyes, weathered noses, and arching backs. In the careful smoothing and exaggerated gestures of these hybrid creatures, a distinctly modern vision of prehistory, myth and the distant future emerges, one worn by time and set beyond the scientific era of discovery and reason. Across their scale and variety, these strange carvings harness a widespread, collective vision to look not at what we understand, but instead at the horrors of the universe, the unconscious, and the unknown.

-

H.P. Lovecraft, O Fortunate Floridian, ed. S.T. Joshi (Tampa: University of Tampa Press, 2007), 13 ↩

-

Miller, Laura, “It’s OK to admit that H.P. Lovecraft was racist,” Salon, accessed 15 November 2016, http://www.salon.com/2014/09/11/its_ok_to_admit_that_h_p_lovecraft_was_racist/ ↩

-

Dennis Rickard, “The Carvings of Clark Ashton Smith,” Eldritch Dark, accessed 15 November 2016, http://www.eldritchdark.com/articles/visual-arts/1/the-carvings-of-clark-ashton-smith. ↩

-

A majority of Smith’s carvings were produced during or shortly after the Great Depression and were, by necessity, made of readily available and cheap materials. These included talc, diatomite, and other soft minerals found in the California hills around Smith’s home in Auburn and, later, near his Pacific Grove house. The carvings were fired in Smith’s kitchen oven to harden the soft stones and provide a burnished surface. Unfortunately, many of the carvings were shattered during this process as the combination of minerals in the rock heated at different rates so that a sculpture would break at its geologic seams. However, Smith’s process of firing in tin cans packed with straw and sand produced a variety of finishes ranging from a dull, blackened appearance to more luminous combinations of blues, greens and pinks. ↩

-

H.P. Lovecraft, O Fortunate Floridian, ed. S.T. Joshi (Tampa: University of Tampa Press, 2007), 404 ↩

-

Rickard, “Clark Ashton Smith: The Artist,” Eldritch Dark, accessed 15 November 2016, http://www.eldritchdark.com/articles/visual-arts/11/clark-ashton-smith%3A-the-artist. ↩

-

As Graham Wilson has pointed out on Eldritch Dark in “Introduction: The Fantastic Art of Clark Ashton Smith “, this presented a problem for Smith’s figurines, which were fragile and difficult to transport. Nevertheless, Smith devised a method of packing. By wrapping them in a pair of socks and shredded newspaper, then placing them inside a tin can within another paper carton and cushioning that with more packing material, he was able to safely ship his carvings across the country. ↩