Time and Space in the Digital World: Critical Views on the Works of Four Colombian Contemporary Artists

/On the evening of December 19, 2016, Russian ambassador to Turkey, Andrei Karlov, was shot dead by a Turkish police officer in the middle of an art gallery opening.[1] The event was recorded from several camera angles; the report quickly spread throughout the world. Similar to other images of war and violence from places distant to our immediate realities, the global memory of this event came to be defined by the cinematic gaze of the camera, the staging of the event, and the simulation we experience through our computer, TV, or smartphone screens. The mediation of the real world through cinematic screens, always more immediate and tightly interconnected than the material reality, alter the very concepts of time and space within the insurmountable confines of the contemporary virtual realities that we inhabit.[2]

The works of four contemporary Colombian artists, which I will be discussing in this article, stem from a reflection of the liminal, material, and visual codes through which the screen produces the images that give us access to knowledge, time, and space. The discussions I’ve had with these four artists, particularly around time and space in the so-called post-internet/information/digital era, aim to understand the possibilities of interrupting/materializing/demystifying/enjoying the stillness of the world through the screen.

Reality and simulation

The physical rules that govern the digital reality that we access through our screens are nothing more than a series of codes that create platforms, which increase and perfect their complexity by users’ interaction. However, this very same digital reality, an essential cog in the simulation machine of the real, also constructs and informs the material/physical/tangible world in which we live in.

In the introduction to Simulacra and Simulations, Jean Baudrillard discusses Borges’ tale, On Exactitude in Science, where cartographers in the empire create a map whose size was that of the empire itself, coinciding with it point for point. Baudrillard uses the tale in order to describe the age of simulacra in which we live in, arguing, “The territory no longer precedes the map, nor survives it. Henceforth, it is the map that precedes the territory—precession of simulacra—it is the map that engenders the territory and if we were to revive the fable today, it would be the territory whose shreds are slowly rotting across the map. It is the real, and not the map, whose vestiges subsist here and there, in the deserts which are no longer those of the Empire, but our own. The desert of the real itself.”[3] The map and the territory are the same thing, constructing each other through our experience of an increasingly virtual reality.

Google Maps, and especially the tool of the street view, is one of the best examples of the ways in which digital mapping constructs our experience of physical territory. Sebastián Cruz proposes an analysis of this phenomenon through his piece Rompe Pantallas (“breaking the screen” in Spanish), which presents a screenshot of a Google Maps view of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Floating Piers installation at Lake Iseo, as the base image for a puzzle.[4] Google Arts and Culture is a platform made for the experience of visual history through the screen, a way of bringing the masses around the world closer to the masterpieces and spaces that they wouldn’t otherwise have access to. The idea of compressing space and thousands of miles of distance into a singular moment on the screen, is tightly connected to the idea of the puzzle. Puzzles traditionally reproduced important art pieces and world wonders, in order to bring them to people’s homes in an interactive and engaging way. The very same spirit is achieved by this Google platform, which works as an already put together puzzle, as pixels load in order to reveal an interactive space made up of 360 degree photographs.

Sebastián Cruz Roldán, Rompe Pantallas, 2016

Sebastián Cruz Roldán is an independent photographer who lives and works in Bogotá. His artistic practice has special interest in collective initiatives. He has been part of Colectivo Invisible (2007–2010) directing a publication and producing performance festivals. In 2008 he co-founded the residency program Residencia en la Tierra that lasted until 2013. Since 2012 he has been part of laagencia, with whom he also co-curated the XIV Regional Artists Salon, zona centro occidente in Bogotá. Cruz manages Ambiente Familiar a photography studio focused in art and architecture.

Cruz’s piece highlights the possibilities of (de)constructing and appropriating reality through digital images of distant places. These images not only mediate our experience of the world but create and perform it, as we experience sites and times we’ve never inhabited. The zenithal[5] scenes provided by Google Street view transform our screens into pseudo-vigilante scopophilic machines[6] with the illusion of going and moving as we please, within the confines of the 9-lens camera Google uses to capture these images. As the title suggests, Cruz’s piece breaks the screen into modular pieces that become interactive and playful; the action of putting the puzzle together mirrors the digital process of putting pixels together to produce an image.

These images from Google Street View also act as frozen photographic simulations of the space that they indicate; they change only every couple of years, allowing us to not only visit distant places but also to travel in time. Time and space are condensed in the experience of the virtual reality of the satellite image, of the lens that captures the “entire world” for our consumption. The screen simultaneously reveals and conceals these geographic and social spaces, transmits and translates, and acts both as the medium and source of knowledge. It is the cinematic apparatus at a global scale. We see the attempt to surpass this with virtual reality video and 360 photography, which allows us to navigate as if we were there. Yet, we can never truly touch the landscape; in other words, the landscape of the world through our screens is inevitably made up of flickering lights and the sound of our typing and clicks.

Space and time

The construction of the digital space is intrinsically dependent on the technologies available to develop it. Green screens in particular, have highly shifted the visual and theoretical reach of virtual worlds, allowing the interchange of spaces and surfaces as well as the correlation between multiple moments in time. The notion of the real, in this case does not necessarily become useless but connotes something else; the space of reality we access through our screens is defined precisely by the malleability of the images at hand. Understanding history through these types of modular images creates portals between the material landscape of said spaces and the virtual imaginaries we relate to reality.

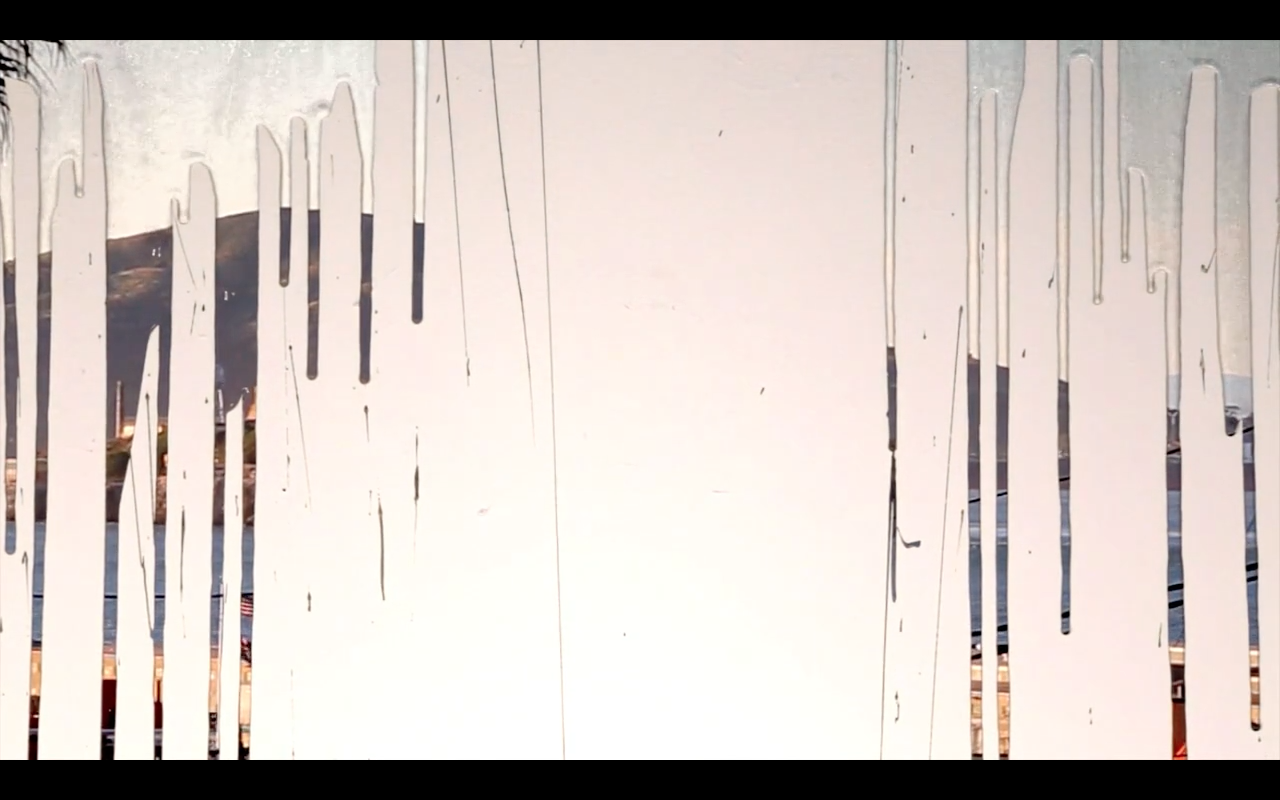

Ana María Montenegro’s Not an Island plays with the sense of (im)possibility that emerges from our distance from digital images, both as simulation and as objects in a constant state of upload through our screens. The video depicts a white wall where dripping green paint used as chroma key,[7] slowly reveals an image of Alcatraz Island, where a historic federal penitentiary still stands. As the paint drips on the wall, a video of the island is slowly revealed. However, the image of the island is never complete. After 59:59 minutes when the white wall disappears and reveals the image on the screen, the shot has performed a total zoom; from the wide angle it started from, to an out of focus extreme close up of the lighthouse.

Alcatraz island bears a significant role in Native American history, as it was the site that symbolized the birth of the Red Power movement after the occupation of the island from 1969 to 1971.[8] Montenegro’s piece denies the full consumption of the island through its simulation, highlighting the impossibility of understanding and fully accessing these historical spaces through digital representation. The denial of understanding implicit in the piece’s title, provides a new reading on what Richard Oakes, leader of the indigenous occupation of the island, once said, “Alcatraz is not an island.” Oakes played with the idea of the island as a symbol of historical relevance, extending far beyond its physicality. In other words, Alcatraz Island was more an idea than what it was an actual mass of land in the San Francisco bay. Montenegro’s reappropriation of Oakes’ idea highlights these tensions between representation and image, reinforcing the political reach and power of the images we construct to understand certain moments in history.

ANA MARÍA MONTENEGRO, NOT AN ISLAND, 2016

ANA MARÍA MONTENEGRO (1986) IS A COLOMBIAN ARTIST BASED IN SAN FRANCISCO, CA. HER WORK IS A SERIES OF CONCEPTUAL EXPERIMENTS THAT DEAL WITH THE PROTOCOLS OF NARRATIVE GENRES, CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CODES, AND THE POLITICAL DYNAMICS THAT AFFECT THEM. SHE MOSTLY USES DIGITAL MEDIA THAT ALLOW HER TO PLAY WITH TIME, TEXT, MOVEMENT, AND RANDOMNESS. HTTP://MONTENEGROJARAMILLO.COM/ TO SEE THE ENTIRE VIDEO, PLEASE VISIT HTTPS://VIMEO.COM/183443945

Montenegro’s piece also provides a reflection on the buffering of reality, ultimately raising the question of time as process and as experience. As one watches, it becomes clear that the purpose is not to unveil truth through the representation of the island, but rather to demonstrate how the imaginary around these spaces is formed, and the ways in which we come to understand time, space, and knowledge through our screens. The screen is transformed into an ideological time-machine, which simultaneously constructs and questions the concept of the real within the scope of so-called post-internet aesthetics. The image we assume will appear—Alcatraz Island—is never presented in its totality, as it also never fully reaches the full hour length in its infinite loop form. The title, denying the very nature of the image and the indicative function of a title, reiterates the clash between meaning and symbol, reverting us back to a virtual world that Baudrillard and Zizek call the desert of the real.

In virtual space we are always online, potentially inhabiting every single space we might want to visit. Compressing time and space through our screens transforms us into quasi omnipresent beings, since we remain bound to our physical bodies sitting down or walking through the streets with our gaze fixed on rectangular monitors. As we become aware of the space it takes to load our images and of the impossibility of consuming them entirely, our understanding of what lies through the black monitor portal becomes even more complex.

Immediacy and rendering

The more immediately we can access the world through the screen-portal, the easier it is to incorporate it into our daily routines. The suspension of this sense of immediacy is thus the ultimate offense, the element of distortion, the glitch that breaks—only to then enhance—the malefice, the simulation. Throbbers, those symbols that appear while we wait for images, websites, and information to load, visualize this suspension of belief. We are distracted with spinning colorful wheels, bars that convey a sense of loading … all placed in order to distract ourselves from the momentary absence and disappearance of the digital space. Similarly, the placeholders in editing softwares such as Photoshop and Illustrator, mark the yet-to-be space where digital space will be filled. However, the X’s that visualize this empty space are only there to prevent the anxiety of an empty digital world.

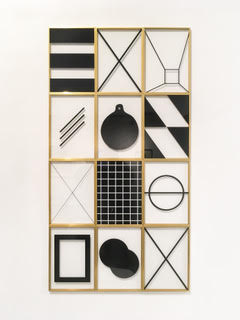

Santiago Pinyol’s Mood Board and The Space Between Things, appropriates the ontology of throbbers and digital placeholders, as the visual metaphors of the waiting space-time that reveals the hidden structure of the web, always loading. As Jack Self argues in his article “Beyond the Self” for e-flux journal, the symbols of the liminal space between users and the images that are potentially consumed or produced through a screen, act as a sign of temporal rupture. Self proposes, “the throbber is thus integral to maintaining the illusion of inescapability, dissimulating the possibility of exiting the network—one that has become both spatially and temporally coextensive with the world. This is the truth of the real-time we now inhabit: a surreal simulation so perfectly smooth it is indistinguishable from, and indeed preferable to, reality.”[9]

The throbber is the sign of an initial rapture, followed by an immediate symbol of the ever-present expectation where indeed something new will appear on our screen. The logic of the screen as portal is haunted by the inevitable blackout, a cessation of the source of power that allows screens to be more than just black unlit monitors that act as perfect mirrors, revealing ourselves as we watch the closed portal.

SANTIAGO PINYOL, MOOD BOARD, 2016

SANTIAGO PINYOL COMPLETED HIS STUDIES IN FINE ARTS AT THE UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE OF MADRID IN 2009, WHERE HE ALSO COMPLETED HIS MASTERS IN ART, CREATION AND RESEARCH IN 2012. HIS WORK IS ORIENTED TOWARDS SELF-MANAGEMENT AS A MODEL, THE IMAGE AS A STRATEGY, AND CULTURE AS A TOOL. HIS INTERESTS REVOLVE AROUND CREATING PLATFORMS, INSTITUTIONS, AND INSTALLATIONS BASED ON EXPERIENCE, CRITICISM, AND IMMATERIALITY. HE HAS WORKED IN COLLECTIVE PROJECTS SUCH A LAAGENCIA, CARNE GALLERY, AND PODERES UNIDOS. WWW.PRODUCCIONINMATERIAL.COM.

The throbber dissimulates this anxiety, over the potential collapse of the virtual world which we inhabit through vision and hearing. It is no wonder that most people popularly call Apple’s spinning color wheel throbber “the spinning wheel of death”. It is the symbol of the collapse of hyperreal space-time, where most of our fast-paced lives happen nowadays. The throbber is also the visualization of the otherwise intangible gap between us and the digital time-space that our screen allows us to enter and inhabit; it is the literal space between things, as the title suggests. Yet, throbbers are simultaneously the break of our time in front of the screen, and the evidence of the gap that enables our hyperrealities to exist in the first place.

The space between things serves two basic purposes; it distances us from the absorption into the simulacra of digital reality, yet it also enables us to see, understand, and imagine what that gap can look like. In other words, we become aware of the malleability of this space. Pinyol’s The Space Between Things plays with this potential of the liminal space, analyzing the placeholders that stand for the yet-to-be images on a screen. These X-marks-the-spot types of visualization provide an understanding of empty digital space, yet fill the void with the demarcation of dimensions and of a potential image. Playing with the composition of these visual placeholders, Pinyol’s piece also highlights the inescapable dynamics of the frame, as the limitation of digital experience; the frame of the screen is the frame of the space-time which we inhabit. It is a sign of the space between us and what digital space could look like, a connection between our bodies and gaze and the world through the screen.

Materiality, or the new map

The fascination we feel while looking at our screens, which shackles our gaze to the light-emitting devices, sucks us into the virtual realities where simulations are our experience of the real; the distinction between both categories becomes null. However, beyond simply being attracted by these lights that produce images in color, we are constantly working in the virtual world we’ve fashioned for ourselves. Every click, scroll, and share, is immediately translated into an input for the insurmountable amount of data that faces us back in the form of surveillance, propaganda, advertising and other self-fulfilling simulacra.

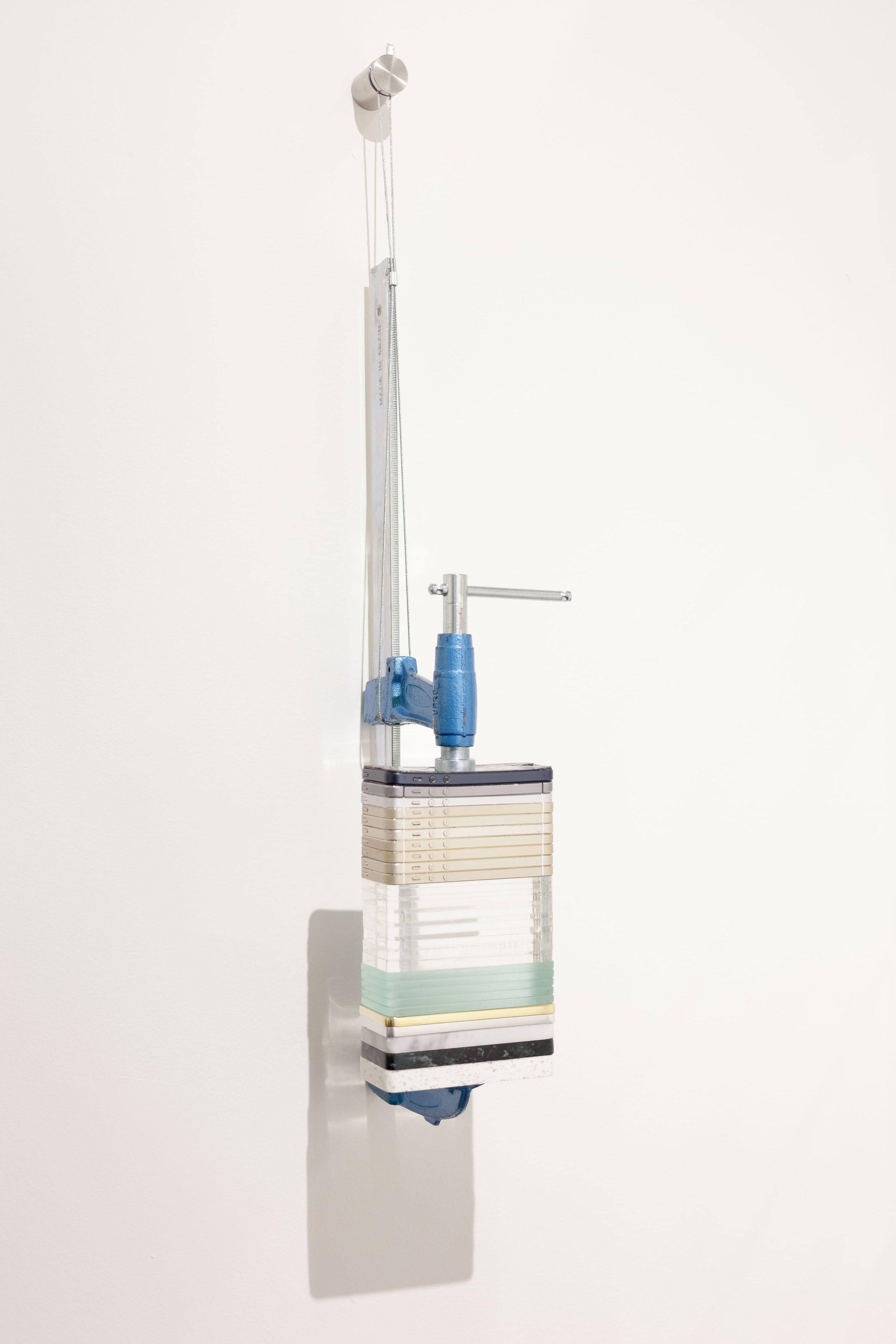

Mariana Murcia’s Scroll is made of broken iPhones and various other materials—plastic, bronze, granite, concrete, marble, glass, acrylic, aluminum, and neon—either cast or cut to the shape and size of the iPhones. All the pieces are arranged in a pile, clamped, and hung from the wall, returning the digital space-time to the geological materiality of the screen. The screen is a product of global mining, neoliberal and unfair labor practices, and dependent on systems of production and distribution that engender one of the fastest growing markets as well as growing e-waste dumpsters. The process of translating electrical impulses and magnetic radio waves into images that are recognizable to us renders our ability to see the screen as a material object almost impossible. The screen as portal into hyperreality forecloses the possibility of understanding the interdependence of the material world and the apparently intangible one we access through our screens.

MARIANA MURCIA, SCROLL, 2017

MARIANA MURCIA (1988) IS A COLOMBIAN ARTIST BASED IN BOGOTÁ. HER WORK DEALS WITH THE SIMULATION OF PHYSICAL SCALE, CREATED BY THE APPARATUS OF IMAGE PRODUCTION AND ECONOMIC SYSTEMS, TRACING THE INVISIBLE CONTOURS OF THE COMPRESSION OF CONTENT INTO FORMS OF COMMUNICATION. OBJECT AND MATERIAL ENSEMBLES LET HER EXPERIMENT WITH CONCEPTUAL FORMS. MARIANA IS ALSO PART OF LAAGENCIA, AN ART PROJECTS OFFICE THAT NURTURES THE RESEARCH AND PROCESSES ON ART+EDUCATION.

The Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) screens of smartphones, act as touchscreens that simultaneously receive and display information. This immediate feedback process, which enhances our experience of appropriating digital space, mirrors the mutually constructive relationship between the material and the digital, the tangible and the intangible, the real and the hyperreal. If we woke up tomorrow and all of our digital technologies were gone, we would still live in a digital world. Not only because the infinitely more complex technology of language has always created a far more sophisticated virtual reality, but because the modes of knowledge we have developed, the way we understand who we are, is intrinsically dependent and constitutive of the media used to express ourselves.

Returning to the tale of the map that is the exact same size of the empire it portrays, Murcia’s work suggests that we are unable to understand land and territory as separate from our digital space. In other words, the digital tools used to understand our place in the world are a fundamental element in the construction of space, as the digital maps themselves outlive the material territories. Just as Google Maps defines our experience and notion of the world we inhabit, and as its archive will survive past the actual destruction of certain parts of our planet, so Murcia’s layers of technology reveal our human history as a geologic array of materials, constituting a sort of parchment paper scroll, which engenders new languages based on the digital time-space. Her work reveals the geological layers of technological waste as the constitution of material sculptural space, a virtual map of reality which survives and supersedes the very notion of our planet.

Here lies the paradox, in which waking up from the dream means waking up in another dream, in an endless cycle and system of simulations, out of which we can only step once the limits of the subject and the language used to describe it are surpassed. The screen is the space between us and the digital worlds we inhabit, not acting so much as a window (a structural object that allows contact between inside and outside) but moreso as a rip or wormhole, where time and space are condensed into an eternal present, a single and constant moment of interaction. The eternal moment when we are online in front of a screen, inhabiting a world where time does not flow but is at a messianic standstill, click after click, it chases us on the streets, on our beds, at work and even in our dreams. It haunts us as the eternal dependency on mining, and the yet-to-come contamination of all of our soils.

The work of Sebastián Cruz, Ana María Montenegro, Santiago Pinyol, and Mariana Murcia, propose an analysis of the cultural moment in which we live, where the dissemination of information depends on the spreading of digital images throughout an almost infinite amount of screens around the world. The map created by these interactions, which would overlay the entire web, reveals the wormhole we are caught in, an altered sense of time and space that is constituting the very understanding of the physical world we inhabit. Seeing this liminal space isn’t easy, partly because we live in it but also because the space between the screen and the physical world lures us into the image as fetish. In other words, images on screens are no longer an index of reality, but are reality itself. Accessing different time zones immediately, leaving voice notes that can be reproduced in an atemporal space, and many of the other features of virtual worlds, disjoint our realities into self-referential and static moments of the present. As the world of the web grows larger, so does the degree to which we exploit and destroy the world in order to create and power the virtual scapes in which we live. Is this capitalism’s worst nightmare—or its most outlandish wishes coming true?

-

http://edition.cnn.com/videos/world/2016/12/19/russian-ambassador-turkey-assassinated-graphic-ath.cnn. ↩

-

Slavoj Zizek, in his book, Welcome to the desert of the real!, analyzes the creation of these virtual realities through the events of September 11 at the World Trade Center in New York. He argues, “we should therefore invert the standard reading according to which the WTC explosions were the intrusion of the Real which shattered our illusory Sphere: quite the reverse - it was before the WTC collapse that we lived in our reality, perceiving Third World horrors as something which was not actually part of our social reality, as something which existed (for us) as a spectral apparition on the (TV) screen—and what happened on September 11 was that this fantasmatic screen apparition entered our reality. It is not that reality entered our image: the image entered and shattered our reality (i.e. the symbolic coordinates which determine what we experience as reality). ↩

-

Zenithal, an adjective linked to zenith, is related to the eye of god, which can see everything. In a map of the world, zenithal indicated a projection where one can identify the direction of any point from the center. ↩

-

Gilles Lipovetsky and Jean Serroy, in their book La Pantalla Global (The Global Screen), argue that the relationship between the screen and cinema is defined by an obsession with the ocular, with the gaze: “In hypermodern culture there is something that can only be called the spirit of cinema and that traverses, waters and nurtures the rest of screens: cinema has become a circle whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere. The more the network, television, video games and spectacles compete with it, the more its essential aesthetic engulfs entire areas of screen culture. The spirit of cinema, the cult to the spectacular visual and famous characters, moves through all of contemporary spectacles, sports, television and a little bit through everything. Infinitely more powerful and global than its native and specific universe, cinema seems to be the contemporary matrix of what is expressed outside of it.” (My translation, 25) ↩

-

Chroma keying is a post-production technique which allows to layer two images or videos, and produce a single composed image using the transparencies generating by certain color hues. The green screen is the most used technique, since selecting and eliminating the chroma range of fluorescent green is easier than any other color. ↩

-

On November 20th 1969, 89 members of the Indians of All Tribes occupied Alcatraz Island demanding self-determination, autonomy, and respect for Indian culture. Their main goal was to expose the marginal condition of Native Americans caused by unjust federal laws and a history of repression, pointing at the government’s negligence towards Indian affairs. At the height of the occupation there were 400 people, yet after 19 months the Indians of All Tribes were forced out by increasing pressure from the Federal Government. Nonetheless, the Occupation had a direct effect on Federal Indian policy and established an important precedent for Indian activism worldwide. ↩

-

Baudrillard, Jean. “Simulacra and Simulations” in Selected Writings. Ed. Mark Poster. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. 166. ↩

-

https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/u/0/entity/m057x7r?hl=es. ↩

-

http://www.e-flux.com/architecture/superhumanity/68658/beyond-the-self/ ↩