Commercial Fantasies: Unpacking the Screen in Advertising

/“How do you explain something you have never seen?” A voice poses this question to the viewer. A woman is shown staring off camera, her expression is relaxed, her eyes are wide, and a soft glow lights her face.

Still from “Sony 4K Ultra HD Smart TV Commercial,” YouTube video, 1:00, from a commercial created by the Sony Corporation, posted by Smart TVs & Gadgets on Aug 5 2014. Accessed March 26 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VsUUwAHXWvA.

“It feels to me like we were watching real life,” chimes another woman. “You have to see it because it is better than real life.”

These comments are the recorded reactions to customers seeing the Sony Corporation’s then-new 4K Ultra HD Television for the first time.[1] In the advertisement, the actual television unit is never shown, inviting the viewer into imagining the “unimaginable” based on the filmed customers’ awe. On its surface, the format seems dramatized. But the verbiage and strategies that Sony uses to seduce customers into curiosity about its product points toward the inconspicuous relationship that we have with electronic visual display technologies, or to state plainly, our screens.

The focus of this essay is to explore the impact of screens as an active agent in the visual experience, altering how we understand, approach, and engage with visual instances both on and off screen. The technological screen’s proliferation in our homes, workplaces, pockets, and public and private spheres, is an example of how the normalization of the screen has altered the physical fabric of our society. Beginning with defining the perceptual and representational assumptions ascribed to screens and screened instances, an alternative approach will be forged focusing on the specificity of the screen as an object and phenomenological site that affects our notions of screen based experience. We spend a miraculous amount of time with our screens. To see it as more than a device for representation considers how its unique style of projection has constructed a specific, technological mode of looking.

So then, what do screens do? To media scholar Lev Manovich, screens function as a portal into a reality separate from our own. Although the content of the screen appears to replicate familiar physical forms, Manovich states that the impossible computer-generated clarity and textures are so specific to the screen that what we see is not a reflection of our reality, but “a realistic representation of a different reality.”[2] The screen uses its representational capacity to produce images we perceive as “realism,” in turn, constructing a visual relationship based in similarity. When the separate synthetic reality masquerades as an enhanced representation of our own reality, the screen’s production of realism doubles as an illusion of indifference. Because the screen represents a reality visually similar to our own, their representations are perceived as being equal, interchangeable, and unaltered.

Considering the screen as a portal to an enhanced version of our physical reality conflates notions of the screen’s representations with that of other screen instances. The mobility of freedom and the ability to exist in multiple iterations and locations is one of the main concepts defining new media and digital objects.[3] Conceivably, once accessed via one screen, the media can be accessed through all screens. Accepting the screen as a portal that provides an improved visual experience is reinforced by the notion that each screen produces the same experience. Yet we must always interface with it through the technological device, as we can never access electronic media without the screen. Although the differentiation may seem to be merely semantic, a conceptual barrier arises when one attempts to parse differences between the screen object and the screen image. When the assumptions of digital and synthetic productions inflect all screen-based media and experience, the perspective of the screen begins to inhibit our engagement with the physical world in which the screen exists.

An example of how screens produce a different synthetic reality can be found again through the Sony Corporation’s advertising in their 2015 commercial for the Bravia 4K Television—a screen that is less than two inches thick.

Still from “Bravia X9000C/X9100C series Floating Style – Our Thinnest ever 4K TV,” YouTube Video, 1:16, Advertisement published by Sony on January 5th 2015. Accessed March 26, 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x5iczT4f17Q.

Immediately, we see the frame of the Bravia television centered upon a sleek table in a sedate room bathed in white. The camera swings wide, revealing the side of the impossibly thin screen propped up by two-pronged feet on its ends. Windows on either side of the room flank the screen; one, frosted, revealing a blurry distant shadow while the other is veiled in a semi-sheer, white curtain, limply tousled by soft wind. The bleakness of the room is juxtaposed by the brilliance of the television’s intensely saturated TRILUMINOS™ color image: an expansive verdant field, replete with rolling mountain range, blue skies, and billowing clouds. The wind depicted on-screen rushing through the empty valley flows in tandem with the wind blowing through an open window to the Bravia’s right. The Bravia’s discrete thinness almost pinches it out of existence, promoting the notion of a screen’s border as obtrusive, attempting to capitalize on a desire to have that obtrusion removed.

The ad seems to seductively whisper that this screen’s ability to replicate the real is so advanced that it tricks nature itself. The Bravia screen’s barely visible frame makes the representations of the screen appear to exist upon the same axis as our physical reality, questioning whether there truly is a separation. The implication is that through its brilliant display, the Bravia is better than reality—depicted as incomparable through the chromatic difference between the dull room and the brilliant picture quality. The enhanced Bravia representations begin to apply cultural theorist Jean Baudrillard’s notion of simulacra, or the adaption of a hyperreal media as a believable and functional, fictitious copy of reality that threatens to replace the real original. [4] Sony’s assumption is that the success of this advertisement will result in the consumer purchasing the Bravia screen. If the rhetoric of the advertisement is that the simulacrum is preferable to reality—in that it looks the same but better—then to purchase the screen is to comply with that assertion. Sony’s marketing and language emphasize a cultural desire for technology to enhance and improve, but not replace—an unnecessary step because they are seen as the same.

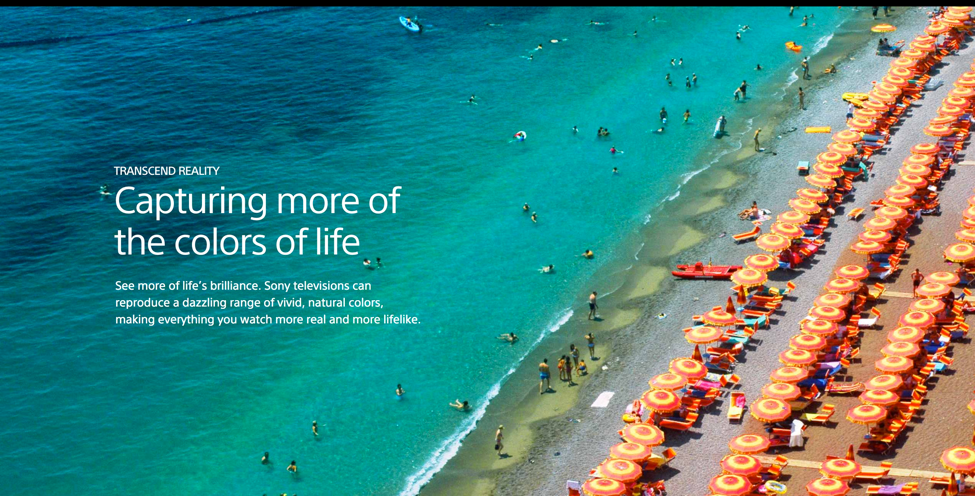

Screengrab from Sony’s website. Sony Corporation of America, 2017. “4K HDR & Full HD Color TVs With TRILUMINOUS Display.” http://www.sony.com/electronics/4k-hd-triluminos-display-color-tvs?cpint=SG_PRODUCT_DETAILS_SEC-TOUT-PDP-X90E-EN_GL-2016-11-M13-DISCOVERWHAT-TOUT03-COLOUR. Accessed May 6 2017.

Without realizing it, the very rhetoric that makes the screen so appealing reveals the cracks in its illusion. Recognizing the screen display as an improved separate reality allows for one recognizing the visual impact of the screen object as an active factor of screen-based visual experiences. First, screen images are always in some way being compared to physical reality, or imbued with our understandings of the physical and tangible; the separation between the two presents a discursive binary that links the physical world and screen-based image. [5] The screen’s objectivity plays into its visual experience, emphasizing an interconnected approach that demands both representational analysis, as well as corporeal or phenomenological engagement.

Second, the separation distinguishes the on-screen representations from the object itself, thus implying that our understanding and acceptance of the screen’s contents are affected by its frame. Until the screen-only Apple iMac desktop computer of the early 2000s, electronic screens have consistently been coupled with a visible computer-processing unit, or CPU tower, or associated with a television. While many of the intricate processes needed to produce an image on-screen are lost to the common consumer, much like the viewers of the Sony 4K television, the awesome capacity that screens possess to create an enhanced version of reality is delivered through the magic of scientific innovation. The connotations of a screen to the science of a computer reinforces its imagery as “correct”—fortified by the rigidity and dependability of numbers.[6] As an object that only produces an image when given an input, the screen’s displays are always successful and proven by the computational system. However, while the canvas and its image bring in different material concerns, the screen’s relationship to computer hardware and digital exactitude reinforces the perception of screen images through its physical vessel.

Thirdly, in framing its contents in these specific modes, the screen ends up contradicting itself. The physical frame contextually presents its contents through the illusion of directness, or an unmediated space. Philosopher Vilém Flusser explains that in order for synthetic images (he refers to them as “technical images”) to successfully appear to us, their mechanical or scientific components must remain hidden and out of view.[7] In order to maintain the illusion of access, enhanced by the computational efficacy of code, the experience of screens assumes a fascination with its surface—that is, the screen must ignore or distract from the difference between image and technological object. This relationship produces a contradiction; the surface can only be made the focus by the screen object itself being acknowledged at some capacity. Accounting for the screen’s object allows one to move away from media specific investigations and approach screen-experiences from a larger discursive space. Unpacking the screen as a site of conflation, illusion, and replication, rooted in its relation to the corporeal and the physical, reveals its larger effects on perception that can be applied to a theorization of the device itself.

The attempt to capitalize on the multiple fallacies of screens remains a ripe commercial opportunity that becomes particularly contentious at its interaction with the visual arts. Over the past couple of years, a multitude of tech start-ups have attempted to capitalize on the ubiquity of screen technologies and its allegedly inherent connection to images.[8]

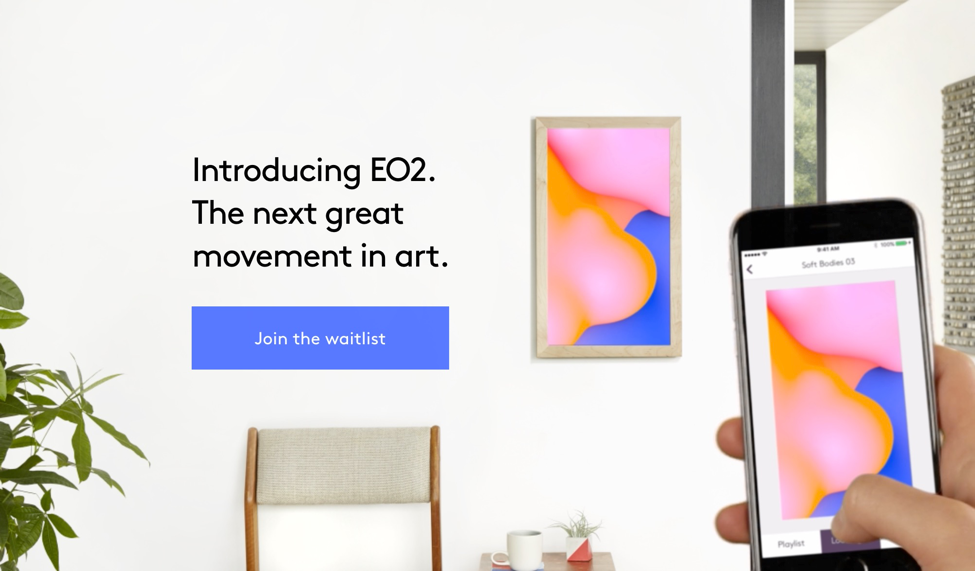

A company called Electric Objects mobilizes the appeal of the internet’s myriad of diverse images, and blends it with a desire to step away from the busyness that our multimedia devices provoke.[9] Their solution is the EO1 and their upcoming EO2 screens—screens specifically designed for enjoying art.

Screengrab of Electric Object’s landing site. Electric Objects, 2017.“The Next Great Movement in Art.” www.electricobjects.com. Accessed March 29 2017.

Meant to “elevate art, and nothing else,” the EO1 re-performs Sony’s argument, again positioning the screen as the key to accessing a better experience for viewing. The physical world is cumbersome and inconvenient, whereas the synthetic screen world is optimized to be easy. Electric Objects promotes their products as “designed to elevate art.” [10] A sleek, plain, and customizable wooden frame allows for the device to match any type of interior. Pairing with multiple physical art institutions, and working collaboratively with Digital artists creating work specific for Electric Objects, a user has complete control over what image is being shown, bolstered by the purported infinity of internet-based choices, and streamlined by the efficiency of a mobile app. With its unobtrusive frame designed to mimic traditional art frames rather than look like a technological screen, the EO1 performs the commercial desire to remove the screen, motivated by a desire for an uninhibited interaction with its electric contents.

Electric Objects’ marketing strategy underlines how the multimedia functionality of our screen devices has produced a need to reduce or limit the experience of screen-usage, while, of course, not moving away from the digital screen itself. The language used to promote their screen as an evolution of art history implies a lack inherently possessed by traditional media that can only be recuperated via technology, propagating and furthering the western canon.

The start-up emphasizes their desire to promote the EO1 screen as a contemplative platform designed to view art in order to escape the overabundance of the web, and the overstimulation native to screen experiences.[11] In their attempts to accentuate the experience of looking, their screen performs the same substitution of a reality with an improved synthetic fantasy provided by the alleged freedom of the internet. The EO1 screen does not substitute a screen image for a physical object, but replaces the corporeal experience of observing an object with the experience of looking at a screen.

Screengrab of Electric Object’s landing site. Electric Objects, 2017. “The Next Great Movement in Art.” www.electricobjects.com. Accessed March 29 2017.

By redefining expectations of screen access, the EO1 inadvertently defines its contents—phenomenological and otherwise—as a product of the screen. In his book The Ecstacy of Communication, Baudrillard discusses the role that the computer terminal plays in effecting our perception. He argues that the potentiality of synthetic images made possible by computer (and by extension screen) technology creates a new mode of viewing: one that is vastly superior to the capabilities of the human body free of hidden qualities or imperfections. [12] He states that when technology presents something to us, it is understood as information: a translation of binary code or computational informatics into a visual representation. His use of the word “information” is key, because it denotes a translation from a physical system into a digital one, and that once rationalized by the computational system and optical efficiency of technology, has been flattened and compressed of any variables. Once it has been turned into information—and Baudrillard’s underlying assertion is that, inevitably, everything will be turned into information—it moves outside of our corporeal limitations into a perceptual model that is constructed but also limited by the capabilities of the technological device. [13]. Electric Objects fulfills Baudrillard’s prediction of a world fully transitioned into digital information, as the EO1’s screen is marketed as the epitome of art viewing. By encasing the collections of physical artworks as products of the EO1—meaning they are only accessible through it—it is translating the physical into information trapped by Electric Object’s screens.

The EO1 performs Baudrillard’s notion of the computer device redefining experience by producing a wholly screen-based experience. In the Kickstarter video for Electric Objects’ EO1 screen, we see how a user would interact with the EO1 in their home.

Electric Objects, “Electric Object: A Computer Made For Art,” Kickstarter video, 1:45, produced by Saint Cloud, accessed March 29, 2017, https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/electricobjects/electric-objects-a-computer-made-for-art.

In her chic living room, the EO1 Screen user pauses in front of an EO1 unit on her wall to casually adjust its image with a few flicks of her phone screen. The actor’s interaction with the two different screens depicts an interesting turn in Baudrillard’s concept of how we interact with technology. Instead of using a singular screen to move us outside of our perceptual limitations through information, the actor uses one screen to manipulate another. Being only accessible through the EO1 and other smart phone or computer screens encases these images specifically within and amongst screens, removing the translation of a corporeal instance into information in favor of information that is being communicated between technological systems. No longer engaging with the physical, the EO1’s relationship to other screens removes the necessity of translating from the physical world.

If the screen is in fact a portal to another reality, then the EO1 shows us that the concepts that currently motivate screen-based experiences are more wholly synthetic (and therefore technologically produced) systems of vision. As we continue to rely on screens, either for the escapism that the Sony Bravia offers or for the contemplative focus of the EO1, we move further away from a dependency on the real as a counterweight to the synthetic or digital. The process of attempting to make media more accessible through technology has successfully obscured its own mediation and effects with the authoritative agency of a secondary technological display. The trappings of assuming the screen does not impose its own logic onto its display—that it does not affect the media it presents—denies the ways in which technology has appointed itself as the new standard for evaluating experience. Today, to imitate real life is to imitate technology. For the time being, the screen will continue to act as a portal to another reality, but we must recognize that reality is already inflected by the perceptual assumptions of other screens.

The issue becomes how to approach the re-structuring of experience into a screen-based template currently replacing pre-existing notions of media, experience, and perception. However, to focus on the screen, to reveal its functions, and to notice its limitations and possibilities, one is able to consider alternatives. If the boundaries between organic and machine, reality and simulation, and physical and digital remain fraught, perhaps it is because of how we approach the issue. Our methodologies, praxis, and explorations must reflect the complicated, integrated, and tangled systems of representation and meaning produced by screen technology and multimedia technological systems. By giving ample consideration to the screen conceptually as an object or material, broader understandings of our relationship to media and technology can be forged.

-

“Sony 4K Ultra HD Smart TV Commercial,” YouTube, 1:00, from a commercial created by the Sony Corporation, posted by Smart TVs & Gadgets on Aug 5, 2014, accessed March 26, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VsUUwAHXWvA. ↩

-

Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001), 202. ↩

-

Christiane Paul, Digital Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 2003), 27. ↩

-

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations, trans. Sheila Faria Glaser (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press), 2. ↩

-

On our relationship to images, Susan Sontag writes: “The primitive notion of the efficacy of images presumes that images possess the qualities of real things, but our inclination is to attribute to real things the qualities of an image.” Susan Sontag, “The Image-World” in On Photography, (New York: Dell Publishing, 1977), 158. ↩

-

Timothy Binkley, “Digital Dilemmas,” Leonardo 3, Supplemental Issue Digital Image, Digital Cinema: SIGGRAPH ’90 Art Show Catalog (1999): 14, accessed April 4, 2017, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1557889. ↩

-

Vilém Flusser, Into the Universe of Technical Images, trans. Nancy Ann Roth (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2011), 35. ↩

-

Alyssa Buffenstein, “Here It Is, Your Guide To Displaying Digital Art,” Vice Creator’s Project, June 24, 2016, accessed March 27, 2017, https://creators.vice.com/en_us/article/8-digital-art-platforms-revolutionizing-the-way-we-view-art ↩

-

“Electric Objects: A Computer Made For Art,” Electric Objects, Kickstarter video, 1:45, produced by Saint Cloud, accessed March 29, 2017, https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/electricobjects/electric-objects-a-computer-made-for-art ↩

-

"Home page," Electric Objects, Accessed March 29, 2017, https://www.electricobjects.com/ ↩

-

Kyle Vanhemert, “A Screen For Bringing The Web’s Most Beautiful Artworks Into Your Home,” Wired, July 8, 2014, Accessed March 29, 2017, https://www.wired.com/2014/07/electric-objects-screen/#slide-id-1221181 ↩

-

Baudrillard, The Ecstacy of Communication, trans. Bernard and Caroline Schutze (Brooklyn: Semiotext(e), 1988), 21–22. ↩

-

Ibid., 23–24. ↩