The Haptic Revolution of Cartographies

/Dead Cartographies and How to Make Them Live[1]

*Note: The video clips and links interspersed throughout the text are meant to be watched and explored as you read through this essay.

“What will you be doing for vacation? Are you going back down there?” asked a university colleague in Italy. “Down? Colombia isn’t so much south, it’s more to the west,” I replied. “Oh, I thought it was in Africa,” he joked.

Years went by, and every time someone referred to my country of origin they used the word giù—down there in Italian. “Ma non torni giù per natale?” (Aren’t you going back down there for Christmas?). “Ma come funzionano giù i treni?” (But how do trains work down there?).” “E i tuoi sono la giù?” (And is your family down there?).

Photograph printed on the top of a box inherited by my grandmother in 2012. Image courtesy of the author.

If we look at a traditional map of the world, it is evident that Colombia is located to the southwest of Italy, yet according to the Italian linguistic configuration, those countries known as “the third world” are to the south, or down there. This notion of down there, if it was cartographically represented, would consist of a different world version than the one we commonly know, allowing us to uniquely place ourselves on planet Earth. Since the objective of this essay is not to explore the complexity and sociocultural issues that arise from the notions of developed vs. undeveloped countries, I will limit myself to state the following question: why, if the Western world has taught us a traditional geographic configuration of planet Earth in a particular way, do Italians insist on linguistically alluding to it differently? I venture to say, ambitiously and daringly, that this statement presupposes a slight failure of cartographies.

Up, down, to the left, to the right, to the north, south, west and east, are notions that derive from an imaginary position vis-á-vis the world when one examines them cartographically, requiring a unique supreme being that observes our planet from afar. Cartographies are, therefore, spatial projections, whose origins are founded in particular sociocultural configurations. And if there are multiple and heterogeneous sociocultural configurations out there, how many possible representations can there be of the space we inhabit?

Anti-palindrome, 2017. Image Courtesy of Felipe Quintero Botero

If we approach planet Earth closely and we don’t visualize the territory as a flattened globe on a flat surface, but more as a city, what would projections of the configuration of urban space entail? Similarly to Earth as a planet, each city makes up an infinite kaleidoscope of configurations—a multiverse—where heterogeneous forces act and manifest themselves through the individuals and their material and immaterial actions within urban space. Similarly, each individual is a multiverse within themselves, and their perception of their surroundings responds to this multiplicity as well. In the city, an infinitude of social relations converge, where urban actors—alive and non-alive, human and non-human—interact and identify with their space, generating both individual and collective knowledge. The experience of public and private occurs in cities, as well as the experience of interior and exterior. These daily rhythms and dynamics built from sometimes novel and impermanent rules, create both individual and collective memories, and become a form of identity. This is an interstitial space, merging the one and the other, constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing complex (and sometimes nonsensical) relations between individuals who inhabit various geographic locations.

How could a cartography respond to the complexity and multiplicity that exists in urban spaces? Could there be a cartography that includes the social dynamics of a urban dwelling? Might this solution promote the possibility to breathe new life into cartographies that no longer serve us?

Fluid Intentions, But Solid Procedures

According to the Italian geographer Franco Farinelli, the classical term for projection—that is the expelling, extending, stretching and pushing forward of something—makes reference to the relentless mechanism that reduces and flattens reality inside the two-dimensional surface of the paper. Generally speaking, cartographies represent the possibility of giving dimensions to land, sea, and space by measuring their physical properties; permitting humankind to control and visually comprehend the configurations that shape urban landscapes. Cartographies can also make visible urban morphologies and their relation to a particular territory; they permit us to satisfy our ocularcentric will to ultimately control, resulting in allowances for conventional and common language to communicate and distinguish aspects of reality in an apparently universal and objective way.

Sections, planes, elevations, site maps, and axonometrics are useful abstractions, but as abstractions, they presuppose a hierarchical ordering of values. As argued by Farinelli, measurability and scale presuppose calculable rationalization as the unique principle that establishes what is included and left out from cartographies, ultimately foreclosing the possibility of any different logic.[2] Scale not only shapes the represented, but also the non-represented, since reducing the real to the measurable implicates the assumption of measurability as the criterion for the existence or nonexistence of spatial elements.[3] The choice to represent some aspects and neglect others is sometimes a conscious decision, other times an unconscious one, depending on the graphical, computational, and technical capacities of a person who subjectively filters the information received from the city or certain territory. Hence some aspects inevitably become erased during cartographic processes.

Mainstream cartographies are not objective; they simplify, generalize and constitute static representations, without taking into account the turbulence and temporality of urban life. Each constitutes an artificial model of reality, an artificial code of interpretation that embraces solely physical facts, but tremendously ignores humans, non-humans, and the non-physical aspects of the city by completely excluding the expression and presence of these more sensorial aspects. According to Farinelli, the modern-age passage from the concrete to the abstract caused by the abandonment of perspective as the main representation technique, as well as the consequently prevalent use of the plane perpendicular to that of our view to project the city, implicates the transition from personal to impersonal, and the evident dehumanization of images, in which it’s not so easy to recognize familiar elements or experience any sort of identification process.[4]

Multi-scalar and Multi-sensory (Re)presentations

While writing this text, I present a significant change of scale; I move from planet Earth to the city: an urban space. This unidirectional movement, which responds to a hypothetical method of deduction, produces an understanding of a wider context, giving us the possibility of establishing logical consequences, a solid and rational structure that seems to be in harmony with everything, with the 'whole', with 'totality'. The directionality from macro to micro satisfies our will to control, order, and catalogue the complexity of space. Nevertheless, a systematic acknowledgement of the polymorphism and pluri-dimensionality of socio-spatial relations requires the multi-directional and multi-scalar recognition of their internal and external contradictions, conflicts, exclusions, and mutabilities.[5] A unidirectional approach cannot be the only way to explore and apprehend the interdependent relations between places and contexts that exist and mutate simultaneously within different scales.

“This is a world which we can only partially understand”[6], a statement by the meticulous geographer, Nigel Thrift, implies that the study of the city cannot apply 'unique', 'certain' or 'ideal' approaches and representations to urban phenomena. The impossibility of capturing the totality of urban life and the evident failure when declaring any representation as 'objective' recalls the necessity of an alternative and more coherent approach regarding urban space complexity. The Non-Representational Theory, composed by Thrift, criticizes the wrongly presumed 'certainty' of mainstream representation—including geographical work based on cartographies—and argues that the social phenomenon of the city should be affronted through the active embrace of movement, impermanence and mutability. Capturing the 'onflow' of everyday life, the concentration on practices, the recognition of things as active and significant parts of 'hybrid assemblages'; the necessity of experimenting, the apprehension of affects and pre-cognitive characteristics, and an 'instinctive' understanding of space constitutes the main presumptions of Non-Representational Theory.[7]

Sensing The City

David Howes, 1991. image courtesy of the author.

The whole body, not only our eyes, should be understood as the center of our world, and as the main focus of perception and representation of the city. We see, touch, smell, taste, and hear our surrounding realities. Our bodies perceive and construct identities, references, and memories accordingly to five, six or seven senses. Sometimes, walking on the street I smell the fragrance of a distant place and a spontaneous reconstruction within the imagination occurs; textures, sounds, flavors and images evoke unexpected relations, feelings, emotions and memories. I feel the contact of my feet walking along foreign city streets and unwittingly, I taste its exotic flavors; I visualize its buildings, its voids, its pathways; I hear its people, their movements, their sounds, their unintentional melodies, their constant tremble and crashing. I sense, I re-create, I remember, I experience again and again in both present and distant places.

Despite the richness and endless possibilities of sensory experiences, the visual paradigm is the prevailing condition for those who design streets, canals and various public infrastructures. The mainstream representations of spaces and the understanding of the city are consequently incoherent or misaligned with the multiple, infinite, multi-scalar and multi-directional possibilities of identifications that exist in space and time. These include identifiers not only expressible, personal and emotional, but also inexpressible, affectual and interpersonal. I dare say that creating only visible, static and unitary representations within city projects and development plan will ultimately lead to arbitrary and anesthetic nuances. The necessity to control and comprehend the urban is our excuse for ignoring and neglecting the in-apprehensible, the untouchable, the invisible, as philosopher Michael David Levin affirms:

"The will to power is very strong in vision. There is a very strong tendency in vision to grasp and fixate, to reify and totalize: a tendency to dominate, secure, and control, which eventually, because it was so extensively promoted, assumed a certain uncontested hegemony over our culture and its philosophical discourse."[8]

Breaking away from ocularcentrism would presuppose a possible solution to the arbitrary nature of cartographies, if we are aiming to include the constant performance of urban life and the multiple possibilities of identification one can experience as the basis for representation. Is it possible then to create an auditory, gastronomical, olfactory or tactile cartography? In order to imagine this, I propose another change of scale: immersion, where one can only taste, hear, smell and touch the city through being physically surrounded by it.

To explore some projects that apply such approaches, go to Cartophonies, Sonic places Berlin, and Sonema

Screengrab from CRESSON (urban research laboratory in France), that contains multiple sound fragments of different cities of the world. Image courtesy of the Author. http://www.cartophonies.fr/

Screengrab from CRESSON (urban research laboratory in France). when exploring in the map Bogotá’s public spaces. Each red dot contains a sound fragment of the urban ambiance of the specific place. Image courtesy of the Author. http://www.cartophonies.fr/

Creating a cartography beyond the visual requires being part of the context, exploring it from the inside, being an insider and an outsider simultaneously. It also means touching, smelling, tasting, hearing and consciously watching the infinite entities and characteristics that are usually ignored, covered, veiled or removed. Sounds and smells are elements commonly considered annoying and distasteful, often unworthy of being included in the creative process of designing and mapping a city. Dust and dirt are automatically associated with poverty and degradation. A strong tendency to clean these types of characteristics is evident among daily human practices. However, immersing oneself in an urban space requires recognizing and receiving stimuli that might be considered toxic. Touch and embodiment are processes that require accepting the social heterogeneity and inequality of the world; performing a haptic immersion can be a political act.[9] Letting go, isolating oneself, and embracing the exteriority of the body as an observer, is interrupted when someone decides to touch urban space with all their senses.

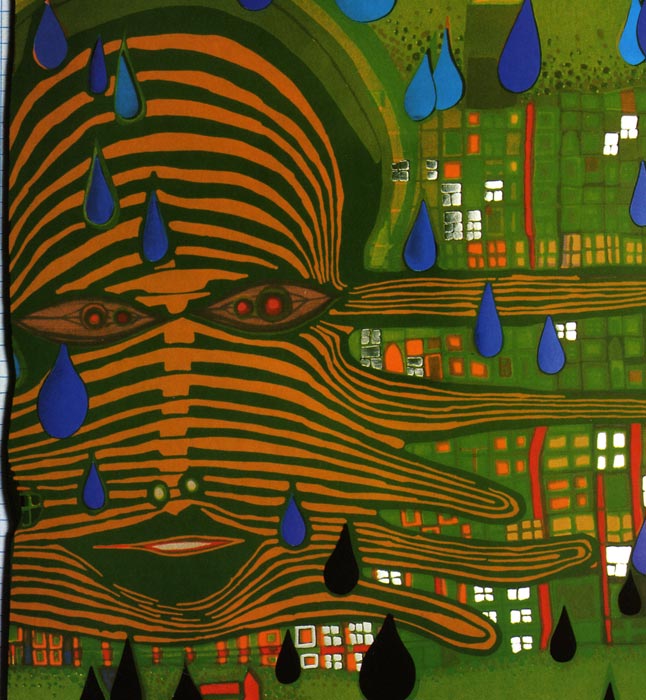

Friedensreich Hundertwasser, Green Power, 1972. Image courtesy of the Author

(Re)presenting the City

How can we capture and represent the life and flow of a city without directing or deteriorating its spontaneity? How does one translate a feeling within a territory into other representational languages without eliminating the immersive experience of that urban space? An effort to present as opposed to represent can be a key exercise to generate innovative strategies in representational tools and methodologies.[10] By focusing less on the categorization of city happenings, and avoiding the tendency to prescribe certain methods or tools as absolute or ideal, and instead, embrace as many of them as possible, there might be room to complement and possibly enhance traditional cartographies with the multiplicity and turbulence they currently omit.

The novelty and random encounters that characterize quotidian life can therefore cross the boundaries that exist between what was felt—as one performs a sensorial immersion in space—and what a distant spectator of a cartography perceives of the represented territory.

In this sense, cartographies that are complemented by texts, photographs, videos, three-dimensional representations, and sound recordings can further evoke the multisensorial experience of an urban space and transform a flat, unidirectional representation into a lively, multifaceted, and animated presentation.

To explore some projects that apply such approaches, click here.

screengrab from Al Centro di Tunisi, a web documentary developed by the interdisciplinary research group GeoTelling. The cartography contains multiple narrations, composed of images, texts and videos. image courtesy of the Author. http://webdoc.unica.it/tunisi/index.htm

research group GeoTelling. The cartography contains multiple narrations, composed of images, texts and videos. when exploring one of the narrations present in the cartography of the Medina quarter of Tunis. image courtesy of the Author. http://webdoc.unica.it/tunisi/index.html

A cartography presents the space of the city when it invited the distant spectator to open all their senses in the same way as the maker of the presentation did, as they entered the reality of the particular space of interest. The distant spectator of these cartographies will not only observe images, or read texts, but will feel the juxtaposition of the different registers of what happens and what is felt, in an array of sensorial modalities. The infinite collage of urban fragments is translated to the language of (re)presentation: multisensorial and moving collages that can construct a presentation of urban space through synesthetic evocations.

An example of this kind of work is the research project “Sensing La Séptima: A Haptic Approach to Urban Practices in Bogotá’s Public Spaces,” whose main methodological proposal is the exploration of public space based on the participatory sensing of urban practices in the pedestrianized street La Séptima in Bogotá, Colombia. The result of a physical, sensorial and emotional immersion over the course of one month of intense fieldwork in 2014 is a haptic geography of “what happens” composed of a fragmented and heterogeneous presentation of La Séptima. Based on the principles of the Non-Representational Theory, this presentation defines the role of public space in the city center of Bogotá at multiple levels and scales, using multiple practices and critical interpretations. The aim of this project is to expose the importance of sensory and emotional approaches to urban spaces as a methodology by including spatial poetics and socio-spatial relations in the study and representation of the city.

To explore this project go to https://sensinglaseptima.wixsite.com/bogota or watch the following video.

The Discovery and Reconstruction of Spatial Poetics

Creative processes that reference or generate spatial representations can be porous and sensitive by existing, moving, and experiencing urban spaces through the lives of its inhabitants and the ways in which they touch, smell, taste, hear, and observe. At the same time, it is through the images created in these processes that the city invents and reinvents itself constantly. Each representation of a city, each cartography, imposes new models and new relations. The ways through which we capture, represent, and re-create our spaces, impose new pieces, new fragments of lively and multidimensional places. Attempting to break the dichotomy between the physical and the immaterial in order to create more open, inclusive, and sensitive representations implies the recognition of spatial poetics that exist in the territory and that are present in the affects, dynamics, and relations that constantly vibrate through that space. Spatial poetics are not configured solely by the physical aspects of a space; they are also constructed by urban life itself, by the rhythms and movements of “what happens” there. Spatial poetics are not closed and static: they are equally open, permeable, and changing like the spaces that compose them. Instead of trying to conquer the city, we should let its poetics conquer us first, so that we can attempt to better (re)present it.

Images from the development of the research project Sensing La Séptima: A Haptic Approach to Urban Practices in Bogotá’s Public Spaces, 2014. Image courtesy of the Author

Bibliography

Amin, Amin., & Thrift, Nigel. (2002). Cities: Reimagining the Urban. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Amin, Amin., & Thrift, Nigel. (2005). Città. Ripensare la dimension urbana. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Amphoux, Pascal. (1991). Paysage sonore urbain: Introduction aux écoutes de la ville. École Polytechinique Fédérale de Lausanne. Institut de Recherche sur l’Environnement Construit.

Cardiff, Janet., & Bures Miller, George. (n.d.). Alter Bahnhof Video Walk. Retrieved from Cardiff - Miller: http://www.cardiffmiller.com/artworks/walks/alterbahnhof_video.html

Crang, Mike. (2003). Qualitative Methods: Touchy, Feely, Look-See. Progress in Human Geography, 4(27), 494–504.

Davies, Gail., & Dwyer, Claire. (2009, May). Qualitative methods III: animating archives, artful interventions and online environments. Progress in Human Geography, 1–10.

Farinelli, Franco. (1992). I segni del mondo: Immagine cartografica e discorso geografico in età moderna. Firenze: La Nuova Italia Editrice.

Fortuna, Carlos. (2009). La ciudad de los sonidos. Una heurística de la sensibilidad en los paisajes urbanos contemporáneos. Cuadernos de Antropología Social(30), 39–58.

Governa, Francesca., & Memoli, Maurizio. (2011). Descrivere la città: metodologia, metodi e techiche, in Geografie dell’urbano. Spazi, pratiche della città (pp. 167–190). Edited by Governa, Francesca, & Maurizio Memoli, Roma: Carocci editore.

Hay, Iain. (2005). Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography (Second Edition ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Howes, David. (2005). Architecture of the Senses. In M. Zardini, & C. C. Architecture (Ed.), Sense of the city: an Alternate Approach to Urbanism (pp. 322–331). Montréal: Lars Müller Publishers.

Jessop, Bob; Brenner, Neil; & Jones, Martin (2008). Theorizing sociospatial relations. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26, 389–401.

Latham, Alan. (2003b). Research, performance, and doing human geography: some reflections on the diary-photograph, diary-interview method. Environment and Planning A, 35, 1993–2017.

Lefebvre, Henri. (2004 (1992)). Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. London: Continuum.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. (2012). The eyes of the skin. Architecture and the senses. Chichester, United Kingdom: Whiley.

Pile, Steve. (2009). Emotions and affect in recent human geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 5–20.

Sonema. (n.d.). Bogotá Fonográfica. Retrieved 05 2014, from Sonema: http://www.sonema.org/bogota-fonografica/

Sonic Spaces (2008). Klang Orte Berlin/Berlin Sonic Places. Retrieved 05 22, 2014, from http://sonic-places.dock-berlin.de/

sonore, C. d. (n.d.). CRESSON. Retrieved 03 2014, from http://www.cresson.archi.fr/

Thrift, Nigel. (2000). Dead geographies - and how to make them live. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 2000(18), 411–432.

Thrift, Nigel. (2007). Non-Representational Theory: Space, politics, affect. London: Routledge.

Cresson. Bogotá Sound Study. Retrieved 03 2014, from http://www.cresson.archi.fr/PUBLI/publiMEDIA/publiMEDIA-bogota.htm

Zardini, Mirko. (2005). Sense of the City: An Alternate Approach to Urbanism. (C. C. Architecture, Ed.)

-

The subtitle references “Dead Geographies - And how to make them live” (Thrift, 2000) ↩

-

Farinelli, Franco. (1992). I segni del mondo: Immagine cartografica e discorso geografico in età moderna. Firenze: La Nuova Italia Editrice. ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

Ibid ↩

-

Jessop, Bob; Brenner, Neil; & Jones, Martin (2008). Theorizing sociospatial relations. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26, 389-401. ↩

-

Thrift, Nigel. (2007). Non-Representational Theory: Space, politics, affect. London: Routledge. 19 ↩

-

Thrift, Nigel. ↩

-

Pallasmaa, Juhani. (2012).The eyes of the skin. Architecture and the senses. Chichester, United Kingdom: Whiley. ↩

-

Howes, David. (2005). Architecture of the Senses. In M. Zardini, & C. C. Architecture (Ed.), Sense of the city: an Alternate Approach to Urbanism (pp. 322-331). Montréal: Lars Müller Publishers. ↩

-

Amin, Amin., & Thrift, Nigel. (2002). Cities: Reimagining the Urban. Cambridge: Polity Press. Crang, Mike. (2003). Qualitative Methods: Touchy, Feely, Look-See. Progress in Human Geography, 4(27), 494-504.Davies, Gail., & Dwyer, Claire. (2009, May). Qualitative methods III: animating archives, artful interventions and online environments. Progress in Human Geography, 1-10.Governa, Francesca., & Memoli, Maurizio. (2011). Descrivere la città: metodologia, metodi e techiche, in Geografie dell'urbano. Spazi, pratiche della città (pp. 167-190). Edited by Governa, Francesca, & Maurizio Memoli, Roma: Carocci editore. Latham, Alan. (2003b). Research, performance, and doing human geography: some reflections on the diary-photograph, diary-interview method. Environment and Planning A, 35, 1993-2017. ↩